Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Candlelight Concerts

This holiday season, I recommend a perfect musical gift to share with loved ones of all ages. Maestro Arthur Shaw presents his beloved "Candlelight Concert" family tradition from Ashland, Oregon and the Midwest to Mercer Island and Bellevue. With a brilliant, new ensemble comprised of respected musical families, Maestro Shaw will present two concerts featuring such cherished favorites as Vivaldi's "Winter from 'The Four Seasons'", Corelli's "Christmas Concerto", and Haydn's "Farewell Symphony" in the elegance of candlelight.

"This is a way of stepping back in time", says Shaw, "and hearing music with just the right ambiance. We'll be recreating a listening experience much like that which would have prevailed in the days when the music was composed. I believe there's nothing that can beat live music in such a romantic setting."

Shaw brings together a roster of formidable players; Ilkka Talvi and Walter Schwede as veteran soloists in Corelli's "Christmas Concerto", and prize-winning young instrumentalists, including cellists Camden Shaw and Karissa Zadinsky, and bassist Derek Zadinsky. It is, in fact, difficult to keep track of these younger players' accolades; they are too numerous. Upon graduation from the prestigious Curtis Institute, and while currently serving as cellist for The Old City String Quartet, Camden's group captured the Grand Prize of the 2010 Fischoff Award. His was chosen out of 48 competing ensembles from across the nation and around the world. Derek Zadinsky, also a recent Curtis graduate, returned in November from touring as a substitute bass player with Cleveland Orchestra. And Derek's younger sister, Karissa, was a winner of the Seattle Symphony Young Artist auditions.

The blend of exceptional youngsters and their established colleagues could be construed as a fusion of past and future; a hope for tomorrow's crop of burgeoning homegrown talent; and an incentive to the entire Eastside region for the support of live music. "Personally, I couldn't help but feel that the loss of Bellevue Philharmonic created a void here," says Shaw. "Bellevue is my community, my home. It is my hope to fill that void. By performing Candlelight Concerts, hopefully, we'll start a new tradition on the Eastside; one that will create a smile in everyone's heart."

Candlelight concerts are planned for 7:30 P.M. Thursday, December 15 at Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Mercer Island, and 7:30 on Saturday, December 17 at St. Margaret Episcopal Church in Bellevue.

Afterglow reception following the concert.

Tickets available at the door: $15 general admission, and $12 for seniors.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Bach Chaconne for Two Violins

|

| photo by Sarah Talvi |

After printing out the score, we played through together, just out of curiosity, and to our delight found the Hermann version most satisfying. Suddenly, four part chords that are often forced or butchered by many violinists of today's era could be rendered with ease and elegance; the underlying harmonies are supported by the second violin with just the right touch of texture, and embellished with flourishes that, I believe, might have pleased old Bach himself. If nothing else, this two violin version of the Bach Chaconne by Hermann might be a godsend for the perplexed teacher, offering a strategy for pacing, polyphony and polish. I nudged my husband to quickly set up the recording equipment, as I know with oncoming holidays, one can put things off indefinitely. I also enlisted the aid of our youngest daughter Sarah as photographer.

It may be helpful to remember that Bach's music fell into relative obscurity after his death. It was Felix Mendelssohn who made Bach's works accessible to the wider public, perhaps rescuing him from oblivion; the general consensus at that time was that Johann Sebastian Bach was nothing more than a musical "mathematician". Mendelssohn published a piano accompaniment to the Chaconne in London and Hamburg in 1847, which was followed a few years later with the accompaniments for all six of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin by Robert Schumann. I eagerly await the experience of studying these!

The venerable concertmaster of the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig, Ferdinand David, immortalized for his premiere of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, introduced the first edited publication of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. However, David was known to have remarked that "he would not be moved by any fee whatsoever to step onto a stage with a naked violin," so terrifying was the thought of performing these works alone. Joseph Joachim was the first daring soul to gather the courage to perform the works without accompaniment, and always did so, which set the standard for our modern day.

Friedrich Hermann, the editor of this two violin version of the Chaconne, was himself a student of Ferdinand David at the Leipzig Conservatory. He also studied composition with Moritz Hauptmann and Felix Mendelssohn.

Ilkka and I dedicate this home production to the memory of Veikko Talvi, who passed away at the age of 100 on October 9, 2011. My dear father-in-law, whose loving spirit will forever remain with us, treasured every note that we played. And then some.

Friday, November 18, 2011

With Head to the Music Bent: A Musician's Story

|

| Randolph Hokanson (photo by MKT) |

As good fortune would have it, I learned a few days later that Mr. Hokanson had just completed and published his memoir: With Head to the Music Bent; A Musician's Story. Instantly I knew that I must get a hold of this book from the author's own hands, and journey with Mr. Hokanson through his years of study with Harold Samuel (one of the first pianists of the twentieth century to focus on the works of Johann Sebastian Bach), English composer Howard Ferguson, Dame Myra Hess, Carl Friedberg (who during his teens studied regularly with Clara Schumann and enjoyed a friendship with Johannes Brahms), and Wilhelm Kempff. I placed a call to the master, and after an invitation for coffee and cake in his studio, I held a beautifully inscribed copy of his memoir.

Mr. Hokanson's gentle and thoughtful narrative rings with as much clarity and insight as his beautiful piano playing. This memoir, with candor and humility, pays hommage to those noble beings who profoundly influenced and shaped his own artistry. In "With Head to the Music Bent," the reader discovers the secrets to contemplative study or what Myra Hess called "complete immersion"; the book guides the reader through the consciousness of sound: "I want to feel that my arm is in the bow, my fingers at the end of it, in direct contact with the strings of the piano."

Mr. Hokanson's gentle and thoughtful narrative rings with as much clarity and insight as his beautiful piano playing. This memoir, with candor and humility, pays hommage to those noble beings who profoundly influenced and shaped his own artistry. In "With Head to the Music Bent," the reader discovers the secrets to contemplative study or what Myra Hess called "complete immersion"; the book guides the reader through the consciousness of sound: "I want to feel that my arm is in the bow, my fingers at the end of it, in direct contact with the strings of the piano."In the late 40's, after an extensive contract with Columbia Artists which led to solo engagements under Sir Thomas Beecham, Pierre Monteux, Arthur Fiedler, Walter Susskind, and Milton Katims, Hokanson was offered a professorship at the faculty of University of Washington. This, in my estimation, might have been the university's musical heyday. The UW faculty included violinist Emanuel Zetlin, cellist Eva Heinitz, violist Vilem Sokol, and conductor Stanley Chapple. Hokanson devotes an entire chapter to his teaching philosophy and principles, most notably: "The ear governs the act". He invokes Myra Hess' dictum, "Think three times before you play a note!".

Mr. Hokanson brings his memoir to a heartfelt coda: "I find now that it needs only a few of the right words to change an attitude or instill a belief—but it has taken a lifetime of engagement with the world to arrive at that simplicity."

His words have taken effect. I returned to Mr. Hokanson's studio today with a pile of music: Bach, Mozart, and Brahms Sonatas. "I prefer to play music with those I love," I told him, and he agreed. We will be meeting for weekly sessions. To hear Randy Hokanson render a phrase is to behold a living link with tradition, all the way back from Carl Friedberg to Schumann and Brahms; an age when more emphasis was given to the principles of correct phrasing than to maximum technical efficiency. We both recognize that time is precious; there's much to accomplish; a new chapter begins.

Thursday, October 6, 2011

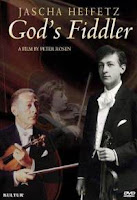

Jascha Heifetz, God's Fiddler

For those Jascha Heifetz aficionados eager to try to crack the code between Heifetz the violin god and Heifetz the man, there's a recent documentary Jascha Heifetz, God's Fiddler, based on Ayke Agus' personal account Heifetz as I Knew Him, produced by Peter Rosen, currently available on DVD. This film cannot claim to present an unbiased comprehensive examination of the artist, for many of Heifetz's peers and colleagues are long dead, and a number of former students were traumatized by their experiences with Heifetz as teacher, as to withhold comments. Furthermore, it would have been intriguing to have heard from one of the Heifetz children. But "God's Fiddler" is certainly an engaging dramatization of Agus' book. For the last fifteen years of Jascha Heifetz's life (he died in 1987), Ayke Agus was his closest companion. She came to him as a student of the master class at the University of Southern California, and ultimately became his private accompanist and confidante.

"God's Fiddler" displays several scenes on location at the Vilna Conservatory, Imperial Concert Hall, and the old Jewish ghetto, which help to recreate young Heifetz's steps, right down to the spot where he played soccer moments before an important debut. Jascha's father, Ruven, was employed as lead violinist for the Vilnius Theater Orchestra, and had Jascha enrolled at the Vilna Conservatory under the tutelage of Ilya Malkin, a former Leopold Auer student. By age seven, it became apparent that Jascha had outgrown Professor Malkin. He was granted an opportunity to play for Auer, the greatest violin pedagogue in all of Russia. Auer, though reluctant at first to hear another "child prodigy" was astonished by the boy. He invited Jascha Heifetz to study with him in St. Petersburg.

But these were troubled times for the Jewish population. City authorities created strict quotas for Jews in St. Petersburg. Composer Alexander Glazunov, head of the conservatory, allowed young Heifetz into the school at the behest of Professor Auer, but whenever Jascha's father left St. Petersburg to return to Vilna to visit his wife and two daughters, Jascha, was warned to remain silent in their one-room flat. If discovered without a proper permit, the consequences might have proved terrifying.

But later, Professor Auer, devised a plan to have Ruven Heifetz, then forty, also admitted into the St. Petersburg Conservatory as a student alongside his son. There are numerous shots of the interior of St. Petersburg Conservatory, up the grand marble staircase, and right into the Auer classroom itself. During one episode at the conservatory, we hear Heifetz's rendition of the Sibelius Violin Concerto. This work would obviously not have been played in Russia at that time, as Sibelius' concerto represented the Finnish nationalistic spirit. But it was indeed Jascha Heifetz who transformed the under-appreciated work into a prized piece of repertoire; Heifetz's performance of the final movement is demonically fast paced, contrary to the composers' wishes, but electrifying to listeners.

"God's Fiddler" treats the viewer to never-before-seen footage of Heifetz as a teenager. By this time, with high fees for concerts, the Heifetz family enjoys a luxurious dwelling in the city. As the political agitation grew to fevered pitch in St. Petersburg, and demands for Heifetz to perform in America increased, Heifetz bought a camera prior to leaving St. Petersburg. He took a photo of the turmoil right outside their St. Petersburg apartment from his window. In the supplemented archival footage, people are seen desperately scurrying on the streets; they resemble ants moving in every different direction; this is the oncoming of the Russian Revolution. Heifetz departs with his family for America. After a much anticipated and hugely successful Carnegie Hall debut, Jascha Heifetz becomes an overnight celebrity; a household name. History would make America my new home, he writes in one of his diaries.

While concertizing in exotic places, he brings his camera. Shown on "God's Fiddler" are captivating shots of Heifetz acting and directing in his home movies. There is also a poignant scene of Heifetz poring over a score with Professor Auer, and my personal favorite: a rare clip of Heifetz performing in front of Helen Keller; her hands every bit as expressive as his while holding Heifetz's violin scroll; Keller's face is radiant while sensing the vibrations.

The film brings to light Heifetz's personal crusade against air pollution (he owned the first modern electric car, a modified Renault) and his relief work during World War II. Forever intrigued by innovation and gadgets, it is documented, but not shown on this film, that Heifetz had a violin crafted out of aluminum to withstand the corrosive, salty air of tropical climates. While performing for troops ready to land in Africa during the Second World War, Heifetz offered unaccompanied Bach to his audience. Bach, Heifetz explained to the troops, might not be to their taste but could be thought of as musical salt. After his performance, a silence ensued, followed by a yell from the back: More salt!

Less understood, and perhaps mystifying, was the deterioration of the Heifetz master class during his late years. One would imagine that students from all over the world would have sought after Heifetz as a teacher. But Heifetz's reputation for being intimidating, and at times downright abusive, caught up with him. A reader of my blog, who was a student of Heifetz in the 80s, shares a frighteningly dysfunctional scene. A talented student performed in class during that year and was made to sit down. Heifetz said: Look at everybody watching you. They are all smiling, but inside they think you are the worst player; they are laughing inside at you. Perhaps, by this time, the great violinist was losing it.

"Jascha Heifetz, God's Fiddler" is a captivating film. It may serve to illustrate the high cost of perfectionism.

"God's Fiddler" displays several scenes on location at the Vilna Conservatory, Imperial Concert Hall, and the old Jewish ghetto, which help to recreate young Heifetz's steps, right down to the spot where he played soccer moments before an important debut. Jascha's father, Ruven, was employed as lead violinist for the Vilnius Theater Orchestra, and had Jascha enrolled at the Vilna Conservatory under the tutelage of Ilya Malkin, a former Leopold Auer student. By age seven, it became apparent that Jascha had outgrown Professor Malkin. He was granted an opportunity to play for Auer, the greatest violin pedagogue in all of Russia. Auer, though reluctant at first to hear another "child prodigy" was astonished by the boy. He invited Jascha Heifetz to study with him in St. Petersburg.

But these were troubled times for the Jewish population. City authorities created strict quotas for Jews in St. Petersburg. Composer Alexander Glazunov, head of the conservatory, allowed young Heifetz into the school at the behest of Professor Auer, but whenever Jascha's father left St. Petersburg to return to Vilna to visit his wife and two daughters, Jascha, was warned to remain silent in their one-room flat. If discovered without a proper permit, the consequences might have proved terrifying.

But later, Professor Auer, devised a plan to have Ruven Heifetz, then forty, also admitted into the St. Petersburg Conservatory as a student alongside his son. There are numerous shots of the interior of St. Petersburg Conservatory, up the grand marble staircase, and right into the Auer classroom itself. During one episode at the conservatory, we hear Heifetz's rendition of the Sibelius Violin Concerto. This work would obviously not have been played in Russia at that time, as Sibelius' concerto represented the Finnish nationalistic spirit. But it was indeed Jascha Heifetz who transformed the under-appreciated work into a prized piece of repertoire; Heifetz's performance of the final movement is demonically fast paced, contrary to the composers' wishes, but electrifying to listeners.

"God's Fiddler" treats the viewer to never-before-seen footage of Heifetz as a teenager. By this time, with high fees for concerts, the Heifetz family enjoys a luxurious dwelling in the city. As the political agitation grew to fevered pitch in St. Petersburg, and demands for Heifetz to perform in America increased, Heifetz bought a camera prior to leaving St. Petersburg. He took a photo of the turmoil right outside their St. Petersburg apartment from his window. In the supplemented archival footage, people are seen desperately scurrying on the streets; they resemble ants moving in every different direction; this is the oncoming of the Russian Revolution. Heifetz departs with his family for America. After a much anticipated and hugely successful Carnegie Hall debut, Jascha Heifetz becomes an overnight celebrity; a household name. History would make America my new home, he writes in one of his diaries.

While concertizing in exotic places, he brings his camera. Shown on "God's Fiddler" are captivating shots of Heifetz acting and directing in his home movies. There is also a poignant scene of Heifetz poring over a score with Professor Auer, and my personal favorite: a rare clip of Heifetz performing in front of Helen Keller; her hands every bit as expressive as his while holding Heifetz's violin scroll; Keller's face is radiant while sensing the vibrations.

|

| Heifetz with his electric Renault, not a Volvo as the DVD claims |

Less understood, and perhaps mystifying, was the deterioration of the Heifetz master class during his late years. One would imagine that students from all over the world would have sought after Heifetz as a teacher. But Heifetz's reputation for being intimidating, and at times downright abusive, caught up with him. A reader of my blog, who was a student of Heifetz in the 80s, shares a frighteningly dysfunctional scene. A talented student performed in class during that year and was made to sit down. Heifetz said: Look at everybody watching you. They are all smiling, but inside they think you are the worst player; they are laughing inside at you. Perhaps, by this time, the great violinist was losing it.

"Jascha Heifetz, God's Fiddler" is a captivating film. It may serve to illustrate the high cost of perfectionism.

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Questions for Violinist and Pedagogue, Endre Gránát

Endre Gránát, former Assistant Concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, Concertmaster of the Goteborg Symphony, Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition and recipient of the Ysaye Medal, was the premier concertmaster who enabled me to work as a violinist in the Hollywood Film Industry during the 80's, when I was a twenty-something- year-old. It was tough (as in competitive) those days; I had only studied the classical music repertoire and was admittedly wet behind the ears for commercial gigs. Nobody else was willing to hire me for studio sessions; a newcomer might be a risk, but Endre took a chance, believed in my playing, and put me down on his coveted list of first violins.

After viewing this brilliant clip of Endre Gránát performing the Ysaÿe Ballade, I had an impulse to contact him. It's been, perhaps, almost thirty years. Sensing the winds of change in our business, with less and less jobs available, I wondered if Endre had advice for young musicians today, or thoughts about the the shifting work scene. Endre Gránát has been professor of violin at the Royal Conservatory in Goteborg, Sweden, Cleveland Institute of Music, University of Illinois, California State University, Northridge, and the University of Southern California. His most recent project and passion, however, has been the editing of concerti by Wieniawski and Mendelssohn with the inclusion of analytical studies and exercises by Otakar Ševčík.

Endre, what's your take on the business? What is the outlook for classical music?

We need to acknowledge the trend. I'll offer you a parallel. Bookstores. Every bookstore is in trouble, yet people are reading more than ever. Businesses need to come up with new formulas. This is a fact. If audiences don't buy your product, you change the product. Take Los Angeles Philharmonic, for example. There was a time you couldn't fill the hall; you'd look around and find rows and rows of empty seats. And now? The place (Disney Hall) is packed. The orchestra can feature an all Webern concert; doesn't matter, everything sells out; LAPO has a new home and a star on the podium.

What about graduating music students with enormous loans to pay off. How can one secure a job in this economy?

First of all, nobody has a birthright to obtain a job. The main criteria for a musician nowadays might be to fit in; to blend. Of course, it helps to be reliable. In other words, show up and shut up.

That sounds familiar. Contractors used to tell us: You're being paid for your time, not your talent. As you look back over many years in the profession, has the playing style changed?

Enormously. If you selected any one of the great violinists from about 1904 through 1965, and had any one of them audition for a position in an orchestra, they'd be laughed off the stage today. They've been replaced by what I call the New York Squeezers. It's a different sound and style. Totally.

I know what you mean. That's depressing. Why would anyone wish to pursue music as a career?

You don't choose music; music chooses you.

Do years of music study pay back?

In my opinion, music belongs to the things that everyone should study, in school, for instance, you might learn tennis or football. Why not the violin? It adds a dimension to life. Without music, one is impoverished. For instance, watch non-professionals play, and you'll see they're in Heaven. My goodness, what can beat playing chamber music with your buddies and enjoying a bottle of wine?

You've got a point there.

Are you writing my obituary?

No, Endre. Not yet. Can you tell me how the recording scene in Hollywood has changed?

When you worked in the studios, Hollywood musicians could keep their fingers in classical music by playing for regional or community orchestras: Glendale, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, etc. Concerts and dress rehearsals would take place on weekends, and studio musicians recorded on weekdays. Any studio work scheduled for weekends used to pay over scale; that's no longer the case. Sessions nowadays are booked anytime, day or night, Saturday or Sunday, with the result being that one sits by the phone, chews their nails, and is enslaved by the business. But I'm in the enviable position of being my own boss. I accept only the work that appeals to me.

I'm eager to get a hold of your editions of the violin concertos of Mendelssohn and Wieniawski that include the analytical studies by the famous pedagogue, Otakar Ševčík. Tell me about this project.

It's been a goal of mine for a long while. The Ševčík annotations for this repertoire have been unavailable for 75 years. I was trained in my native Hungary by this approach; I know each exercise by heart. Believe me, Ševčík was anal to the thirty second note, writing down nuances for the player, as he had first hand knowledge from the composers themselves. But remember, this manner of transmitting knowledge was prior to recording technology, or the technology was so poor that the analysis was an essential tool. For 19 pages of manuscript you have 97 pages of exercises. But Ševčík taught his students how to learn and how to practice. I was fortunate to have met with Ševčík's pupil, Vilem Sokol, a few years ago in Seattle. I'll tell you what happened. I phoned the Sokol home and was received by his daughter. She said that Vilem would be available for only one hour at lunchtime, given his age and the condition of his health. So, Steve Shipps (who is also editing for this project) and I went to meet Vilem. We expected that after an hour or so, he'd be exhausted, and our meeting would be over. But that wasn't the case. Vilem had a drink with his meal, then another, and another. The Ševčík stories were endlessly entertaining! Before we knew it, the afternoon had long past, and it was around seven o'clock, time for dinner. We stayed and had another round of drinks with another meal.

Vilem Sokol was a luminary; one of the greatest musicians of all times. Sadly, he passed away last August at the age of 96. What a gift to know that we can share Vilem's musical expertise through you, Endre.

And for me to know that I have taught others to learn—this is the most important thing—then I have succeeded.

After viewing this brilliant clip of Endre Gránát performing the Ysaÿe Ballade, I had an impulse to contact him. It's been, perhaps, almost thirty years. Sensing the winds of change in our business, with less and less jobs available, I wondered if Endre had advice for young musicians today, or thoughts about the the shifting work scene. Endre Gránát has been professor of violin at the Royal Conservatory in Goteborg, Sweden, Cleveland Institute of Music, University of Illinois, California State University, Northridge, and the University of Southern California. His most recent project and passion, however, has been the editing of concerti by Wieniawski and Mendelssohn with the inclusion of analytical studies and exercises by Otakar Ševčík.

Endre, what's your take on the business? What is the outlook for classical music?

We need to acknowledge the trend. I'll offer you a parallel. Bookstores. Every bookstore is in trouble, yet people are reading more than ever. Businesses need to come up with new formulas. This is a fact. If audiences don't buy your product, you change the product. Take Los Angeles Philharmonic, for example. There was a time you couldn't fill the hall; you'd look around and find rows and rows of empty seats. And now? The place (Disney Hall) is packed. The orchestra can feature an all Webern concert; doesn't matter, everything sells out; LAPO has a new home and a star on the podium.

What about graduating music students with enormous loans to pay off. How can one secure a job in this economy?

First of all, nobody has a birthright to obtain a job. The main criteria for a musician nowadays might be to fit in; to blend. Of course, it helps to be reliable. In other words, show up and shut up.

That sounds familiar. Contractors used to tell us: You're being paid for your time, not your talent. As you look back over many years in the profession, has the playing style changed?

Enormously. If you selected any one of the great violinists from about 1904 through 1965, and had any one of them audition for a position in an orchestra, they'd be laughed off the stage today. They've been replaced by what I call the New York Squeezers. It's a different sound and style. Totally.

I know what you mean. That's depressing. Why would anyone wish to pursue music as a career?

You don't choose music; music chooses you.

Do years of music study pay back?

In my opinion, music belongs to the things that everyone should study, in school, for instance, you might learn tennis or football. Why not the violin? It adds a dimension to life. Without music, one is impoverished. For instance, watch non-professionals play, and you'll see they're in Heaven. My goodness, what can beat playing chamber music with your buddies and enjoying a bottle of wine?

You've got a point there.

Are you writing my obituary?

No, Endre. Not yet. Can you tell me how the recording scene in Hollywood has changed?

When you worked in the studios, Hollywood musicians could keep their fingers in classical music by playing for regional or community orchestras: Glendale, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, etc. Concerts and dress rehearsals would take place on weekends, and studio musicians recorded on weekdays. Any studio work scheduled for weekends used to pay over scale; that's no longer the case. Sessions nowadays are booked anytime, day or night, Saturday or Sunday, with the result being that one sits by the phone, chews their nails, and is enslaved by the business. But I'm in the enviable position of being my own boss. I accept only the work that appeals to me.

|

| from left: Endre Gránát, Vilem Sokol, Stephen Shipps |

It's been a goal of mine for a long while. The Ševčík annotations for this repertoire have been unavailable for 75 years. I was trained in my native Hungary by this approach; I know each exercise by heart. Believe me, Ševčík was anal to the thirty second note, writing down nuances for the player, as he had first hand knowledge from the composers themselves. But remember, this manner of transmitting knowledge was prior to recording technology, or the technology was so poor that the analysis was an essential tool. For 19 pages of manuscript you have 97 pages of exercises. But Ševčík taught his students how to learn and how to practice. I was fortunate to have met with Ševčík's pupil, Vilem Sokol, a few years ago in Seattle. I'll tell you what happened. I phoned the Sokol home and was received by his daughter. She said that Vilem would be available for only one hour at lunchtime, given his age and the condition of his health. So, Steve Shipps (who is also editing for this project) and I went to meet Vilem. We expected that after an hour or so, he'd be exhausted, and our meeting would be over. But that wasn't the case. Vilem had a drink with his meal, then another, and another. The Ševčík stories were endlessly entertaining! Before we knew it, the afternoon had long past, and it was around seven o'clock, time for dinner. We stayed and had another round of drinks with another meal.

Vilem Sokol was a luminary; one of the greatest musicians of all times. Sadly, he passed away last August at the age of 96. What a gift to know that we can share Vilem's musical expertise through you, Endre.

And for me to know that I have taught others to learn—this is the most important thing—then I have succeeded.

Friday, September 16, 2011

Forbidden Childhood

One of my Frantic readers recommended the book, "Forbidden Childhood" to me by pianist Ruth Slenczyska. He had stumbled across my blog and recognized similarities to Slenczynska's memoir. As it turns out, my reader friend (pianist Andrew Gordon) and I shared concerts together as children growing up outside the Boston area. Oddly enough, I remember warming up backstage for a Jewish Music Forum event, my usual edgy teen-aged self; thirteen-year-old Andrew didn't say a word but just stared blankly while drumming his fingers on his lap. I imagine that I must have paced back and forth in my normal pre-concert jittery style, wiping my sweaty palms on my short skirt before entering the stage to perform an entire Jewish program. My mother had carefully selected the repertoire, excavating all the Jewish composers she could find, including William Kroll. To her, Mendelssohn qualified as a Jew even if his family had been converted and Kreisler also, so "Song Without Words" would have made the grade. "Was Wieniawski really Jewish?" I recall my mother asking while flipping relentlessly through "The Oxford Companion to Music". She discovered that Wieniawski's family, too, had converted to Catholicism. Finally, she settled on Joseph Achron's "Hebrew Melody"as a complement to Kroll's "Banjo and Fiddle". Besides, as young Andrew Gordon was to perform Achron's "Children's Suite" based on cantorial chant for the event, her daughter wasn't to be outdone.

Josef Slenczynska demanded that his daughter practice nine hours daily from the age of four, firing one teacher after the next. Ruth Slenczynska studied with a whole galaxy of legendary pianists: Artur Schnabel, Alfred Cortot, Egon Petri, Josef Hofmann, Nadia Boulanger, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. She made her Berlin debut at the age of six, and performed her full debut in Paris when only eleven years old. By age fifteen, after a shattering emotional crisis which points to her abusive father, she withdrew from the concert stage. Ruth reflects,"Some such turning point arrives in the life of every child prodigy: the day when allowances cease to be made on grounds of youth; the time for reappraisal; the need for readjusting to new values." Fortunately for the musical world, Ruth Slenczynska found her way back into teaching and performing; her wit, miraculously, in tact. Most Wunderkinder have been less fortunate.

From personal experience, those I've known appear haunted, or sometimes almost deranged, by the ghost of the never satisfied stage parent. As an Interlochen alumni, I found this clip of There's Magic in Music (1941) positively enchanting. Much of the movie was filmed on location at National Music Camp. Towards the end of this scene, however, a cameo appearance by violin prodigy Heimo Haitto captivates my attention. In the film Haitto describes himself as a Finnish refugee. It dawns on me that Ilkka has mentioned Haitto's name several times over the years with a mixture of disbelief and compassion. It is documented that during the Russo-Finnish War, Heimo Haitto was sent away by his parents, along with his teacher, Boris Sirpo, to America. But it remains sketchy as to the abuses he suffered by an exploitative entourage. I click on this YouTube performance and my heart melts with the staggering beauty of Sibelius "Serenade" as played by Haitto and the Finnish Radio Orchestra. I scroll down and view a concert from later years. It's one thing to listen to a young boy full of promise, yet another to witness a broken down, aged fiddle player. There is a far away look in Haitto's eyes; as if a flame is about to extinguish. Heimo Haitto's personal struggle was a journey from a forbidden childhood to an almost forgotten life.

I remember wondering how he—Andrew Gordon—exhibited such calm prior to performance. "I get nervous," I might have blurted while practicing backstage. I'm not sure whether I just kept the thought to myself or said it out loud. Alas—forty years—through the amazing internet, Andrew and I have found one another; our e-mail exchanges spill over with anecdotes from the past; words that were stifled in his youth fill the computer screen, including nuanced tales of a particular female teacher who wore too much make-up, sported mini skirts which emphasized her varicose veins, and coddled him like a baby. And it was this teacher who happened to share passages of Ruth Slenczynska's breath-taking memoir with Andrew.

In "Forbidden Childhood" American pianist Ruth Slenczyska (born 1925 in Sacramento) recounts how her father, Josef Slenczynska, a failed violinist took one look at her hands when she was just two hours old and burst into tears.

"Look at those sturdy wrists!" he said between sobs. "Notice the way her thumb is separate from the rest of her hand! Look at the tip of her fingers! I swear to you, Mamma, that's a musician!"

Josef Slenczynska demanded that his daughter practice nine hours daily from the age of four, firing one teacher after the next. Ruth Slenczynska studied with a whole galaxy of legendary pianists: Artur Schnabel, Alfred Cortot, Egon Petri, Josef Hofmann, Nadia Boulanger, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. She made her Berlin debut at the age of six, and performed her full debut in Paris when only eleven years old. By age fifteen, after a shattering emotional crisis which points to her abusive father, she withdrew from the concert stage. Ruth reflects,"Some such turning point arrives in the life of every child prodigy: the day when allowances cease to be made on grounds of youth; the time for reappraisal; the need for readjusting to new values." Fortunately for the musical world, Ruth Slenczynska found her way back into teaching and performing; her wit, miraculously, in tact. Most Wunderkinder have been less fortunate.

From personal experience, those I've known appear haunted, or sometimes almost deranged, by the ghost of the never satisfied stage parent. As an Interlochen alumni, I found this clip of There's Magic in Music (1941) positively enchanting. Much of the movie was filmed on location at National Music Camp. Towards the end of this scene, however, a cameo appearance by violin prodigy Heimo Haitto captivates my attention. In the film Haitto describes himself as a Finnish refugee. It dawns on me that Ilkka has mentioned Haitto's name several times over the years with a mixture of disbelief and compassion. It is documented that during the Russo-Finnish War, Heimo Haitto was sent away by his parents, along with his teacher, Boris Sirpo, to America. But it remains sketchy as to the abuses he suffered by an exploitative entourage. I click on this YouTube performance and my heart melts with the staggering beauty of Sibelius "Serenade" as played by Haitto and the Finnish Radio Orchestra. I scroll down and view a concert from later years. It's one thing to listen to a young boy full of promise, yet another to witness a broken down, aged fiddle player. There is a far away look in Haitto's eyes; as if a flame is about to extinguish. Heimo Haitto's personal struggle was a journey from a forbidden childhood to an almost forgotten life.

Friday, July 22, 2011

The Two Sides of Mahler

I'll admit. It's not easy to get my husband to consent to an interview—on any subject—let alone the topic of Mahler, especially for my blog. But since he served as concertmaster for the Seventeenth Annual Northwest Mahler Festival, under the baton of eighteen-year-old Principal Conductor, Alexander Prior (who, by the way, is a marvel as both conductor and composer), I have Mahler on the brain. Besides, this year marks the centennial of the composer's death.

So, without his actual consent I took notes on the sly and kept a sheet of paper between the pages of Norman Lebrecht's most recent book, "Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World."

Alas! An unauthorized interview with violinist Ilkka Talvi on Gustav Mahler.

I've heard you occasionally compare composers with cuisine. If Beethoven is pasta, as you claim, with long spaghetti-like phrases that sometimes curl, twist and stretch, and Brahms is hearty as a steak or a solid piece of meat, what is Mahler?

Mahler reminds me of Chinese Dim Sum, a meal that lasts for a couple of hours, in which you can't be quite sure what, exactly, you're eating. But that doesn't mean it's not tasty. It's just too much of everything; you might end up with, say, twenty-five different dishes, or a mishmash.

I sense a slight, I wouldn't call it hostility, but an irritation with the excessive performance instructions mandated in the score by Mahler. Explain.

Either Mahler thought the musicians were complete idiots or he felt an intense need to micro-manage every player. For example, there's a long instructive sentence asking to play with utmost force so string vibrates wildly, rubbing against the fingerboard.

So?

For one thing, this result can only be achieved with pure gut strings and a low bridge. How many players today use sheep gut strings? Mahler also specifies "vibrando". You know why?

Is this a quiz?

Orchestras of Mahler's day didn't use vibrato. It was an occasional stylistic device, like an embellishment. That's most likely why the concertmaster of Vienna Hofoper Arnold Rosé, who just happened to be Mahler's brother-in-law, turned down Fritz Kreisler's audition. Kreisler was the first to use constant vibrato in his playing, and the technique was unheard of in those days. As a result, he couldn't get a position in the Hofoper. But today you have orchestras performing Mahler and vibrating like crazy without regard for authenticity.

Your somewhat controversial theory regarding Leonard Bernstein and his promotion of Mahler's music as a means to spur Jewish philanthropic support fascinates me.

The Bernstein/Mahler combination with the New York Philharmonic was a fail proof recipe for philanthropic success. Bernstein was able to prosyletize Mahler, the Jew, by emphasizing his use of Yiddish folk melodies and familiar Klezmer tunes. This music in combination with Bernstein's charisma, galvanized the support of the Jewish community. Jews from the Old Country needed a musical hero, and they got two for the price of one: Mahler and Bernstein. Suddenly Gustav Mahler had become 105% Jewish. Never mind that the composer had converted to Catholicism. Bernstein intuited that his followers yearned to experience something totally fresh and new with regard to repertoire, rather than being subjected to the same German compositions that reminded them of the past. Bernstein sensed this. The Jewish composer Schoenberg, with his twelve tone technique, would've been impossible to digest, but Mahler—

How did you come up with 105%?

Because with Mahler, the megalomaniac, everything is in excess. Orchestras are going broke; the sheer forces needed to perform his music are budget busters. Megaworks. Obviously they're becoming the property of community and youth orchestras in this country, as it's no longer affordable to produce a Mahler Symphony. Same with Wagner, who, by the way, in spite of his vituperative antisemitic statements about Jews in music, Mahler venerated. Conducting Wagner's music was Mahler's ticket to fame, like the Israeli conductor, Asher Fisch. It all started with Wagner's disdain for Felix Mendelssohn. All because Mendelssohn didn't give Wagner the time of day. Which leads to the paradox; Mahler and his adoration for Wagner.

You seem bothered.

You know what really gets under my skin?

What?

The main thing that annoys me is that all these composers (Mendelssohn, Mahler, and even dear old Fritz Kreisler) were in a hurry to deny their cultural heritage and adopt Catholicism for self-advancement. Putting it simply, Mahler changed his religion in 1897 to get a better gig with the Vienna Court Opera.

You know, I have a vision of Hell.

Oh, what is it?

Richard Wagner is forced to conduct an all Mahler festival, with all ten symphonies, endlessly played by musicians of certain ethnic backgrounds. They have no common language, so the German terms are meaningless. And every single part in the score has been re-orchestrated by Mendelssohn!

What if Mahler were a conductor or music director of a professional American orchestra today; how do you imagine players would react?

They'd go on strike. First of all, Mahler would insist on featuring his symphonic works with endless rehearsals and impossible over-time. And, especially today, orchestra musicians would not tolerate his asinine, autocratic behavior. Most important, they'd expect him to show his directives with the stick, not overload them with verbal commands: "breathe here, slow down there, intermission here to wipe your arse."

Do you think that Mahler would have made a successful fund raiser?

Hell raiser—is more like it.

In a review of Norman Lebrecht's "Why Mahler" by Leon Botstein for the Wall Street Journal, Botstein makes the point that a "troubling aspect of Lebrecht's chronicle is the importance he gives to recordings. Although Lebrecht recommends hearing Mahler in live performance, one senses his passion for Mahler is linked to his experience of listening to the composer's music with headphones or in front of the loudspeakers." What are your thoughts about live versus recorded Mahler performances?

Recordings are an ideal way to listen to the works of both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Being that they were conductors, and heard their works performed from the vantage point of the podium, they lacked the same aural experience as the concert-goer. For Strauss and Mahler it was up close and personal. When Strauss composes a solo marked "lowest notes sul G in piano" for the concertmaster and the brass is playing at the same time, Strauss's conception was for the violin solo close to his ear, rather than afar, as one can hear on a recording.

In "Why Mahler?" Lebrecht features an exchange between your Finnish countryman, Jean Sibelius, and Gustav Mahler. They apparently met one time in Finland. Sibelius, who had completed his own Third Symphony extolled the virtues of structural severity. Mahler countered Sibelius with his belief that the symphony must be like the whole world, insisting that a symphony must embrace everything.

And see what happened? Mahler died at age fifty-one and Sibelius (who stopped composing around the same age) lived into his nineties.

Mahler suffered from terrible hemorrhoids.

Mahler was a hemorrhoid. He treated his musicians horribly.

You most recently performed Mahler's Third Symphony, and without going overboard, I'd say your solos were divine. In this symphony, Mahler sought to explain the universe, to find a reason for suffering and misery in this world. Some believe the answer to solving the Mahler riddle might be revealed in Schopenhauer's "The World as Will and Representation," as Schopenhauer's philosophy captivated the composer. For Bernstein, the Third Symphony was not just a pastoral symphony—an answer to Beethoven, but an ecological prophecy. In 1967, Bernstein claimed that it is 'only after we have experienced the smoking ovens of Auschwitz, the frantically bombed jungles of Vietnam, through Hungary, Suez, the Bay of Pigs, the refueling of the Nazi machine, the murder in Dallas, the arrogance of South Africa, the Hiss-Chambers travesty, the Trotskyite purges, Black Power, Red Guards, the Arab encirclement of Israel, the plague of MacCarthyism, the Tweedledum armaments race—only after this can we finally listen to Mahler's music and understand that it foretold all'.

So tell me. What was your favorite moment in the performance of the Third Symphony?

When it was over.

So, without his actual consent I took notes on the sly and kept a sheet of paper between the pages of Norman Lebrecht's most recent book, "Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World."

Alas! An unauthorized interview with violinist Ilkka Talvi on Gustav Mahler.

|

| The Two Sides of the Critic |

I've heard you occasionally compare composers with cuisine. If Beethoven is pasta, as you claim, with long spaghetti-like phrases that sometimes curl, twist and stretch, and Brahms is hearty as a steak or a solid piece of meat, what is Mahler?

Mahler reminds me of Chinese Dim Sum, a meal that lasts for a couple of hours, in which you can't be quite sure what, exactly, you're eating. But that doesn't mean it's not tasty. It's just too much of everything; you might end up with, say, twenty-five different dishes, or a mishmash.

I sense a slight, I wouldn't call it hostility, but an irritation with the excessive performance instructions mandated in the score by Mahler. Explain.

Either Mahler thought the musicians were complete idiots or he felt an intense need to micro-manage every player. For example, there's a long instructive sentence asking to play with utmost force so string vibrates wildly, rubbing against the fingerboard.

So?

For one thing, this result can only be achieved with pure gut strings and a low bridge. How many players today use sheep gut strings? Mahler also specifies "vibrando". You know why?

Is this a quiz?

Orchestras of Mahler's day didn't use vibrato. It was an occasional stylistic device, like an embellishment. That's most likely why the concertmaster of Vienna Hofoper Arnold Rosé, who just happened to be Mahler's brother-in-law, turned down Fritz Kreisler's audition. Kreisler was the first to use constant vibrato in his playing, and the technique was unheard of in those days. As a result, he couldn't get a position in the Hofoper. But today you have orchestras performing Mahler and vibrating like crazy without regard for authenticity.

Your somewhat controversial theory regarding Leonard Bernstein and his promotion of Mahler's music as a means to spur Jewish philanthropic support fascinates me.

The Bernstein/Mahler combination with the New York Philharmonic was a fail proof recipe for philanthropic success. Bernstein was able to prosyletize Mahler, the Jew, by emphasizing his use of Yiddish folk melodies and familiar Klezmer tunes. This music in combination with Bernstein's charisma, galvanized the support of the Jewish community. Jews from the Old Country needed a musical hero, and they got two for the price of one: Mahler and Bernstein. Suddenly Gustav Mahler had become 105% Jewish. Never mind that the composer had converted to Catholicism. Bernstein intuited that his followers yearned to experience something totally fresh and new with regard to repertoire, rather than being subjected to the same German compositions that reminded them of the past. Bernstein sensed this. The Jewish composer Schoenberg, with his twelve tone technique, would've been impossible to digest, but Mahler—

How did you come up with 105%?

Because with Mahler, the megalomaniac, everything is in excess. Orchestras are going broke; the sheer forces needed to perform his music are budget busters. Megaworks. Obviously they're becoming the property of community and youth orchestras in this country, as it's no longer affordable to produce a Mahler Symphony. Same with Wagner, who, by the way, in spite of his vituperative antisemitic statements about Jews in music, Mahler venerated. Conducting Wagner's music was Mahler's ticket to fame, like the Israeli conductor, Asher Fisch. It all started with Wagner's disdain for Felix Mendelssohn. All because Mendelssohn didn't give Wagner the time of day. Which leads to the paradox; Mahler and his adoration for Wagner.

You seem bothered.

You know what really gets under my skin?

What?

The main thing that annoys me is that all these composers (Mendelssohn, Mahler, and even dear old Fritz Kreisler) were in a hurry to deny their cultural heritage and adopt Catholicism for self-advancement. Putting it simply, Mahler changed his religion in 1897 to get a better gig with the Vienna Court Opera.

You know, I have a vision of Hell.

Oh, what is it?

Richard Wagner is forced to conduct an all Mahler festival, with all ten symphonies, endlessly played by musicians of certain ethnic backgrounds. They have no common language, so the German terms are meaningless. And every single part in the score has been re-orchestrated by Mendelssohn!

What if Mahler were a conductor or music director of a professional American orchestra today; how do you imagine players would react?

They'd go on strike. First of all, Mahler would insist on featuring his symphonic works with endless rehearsals and impossible over-time. And, especially today, orchestra musicians would not tolerate his asinine, autocratic behavior. Most important, they'd expect him to show his directives with the stick, not overload them with verbal commands: "breathe here, slow down there, intermission here to wipe your arse."

Do you think that Mahler would have made a successful fund raiser?

Hell raiser—is more like it.

In a review of Norman Lebrecht's "Why Mahler" by Leon Botstein for the Wall Street Journal, Botstein makes the point that a "troubling aspect of Lebrecht's chronicle is the importance he gives to recordings. Although Lebrecht recommends hearing Mahler in live performance, one senses his passion for Mahler is linked to his experience of listening to the composer's music with headphones or in front of the loudspeakers." What are your thoughts about live versus recorded Mahler performances?

Recordings are an ideal way to listen to the works of both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Being that they were conductors, and heard their works performed from the vantage point of the podium, they lacked the same aural experience as the concert-goer. For Strauss and Mahler it was up close and personal. When Strauss composes a solo marked "lowest notes sul G in piano" for the concertmaster and the brass is playing at the same time, Strauss's conception was for the violin solo close to his ear, rather than afar, as one can hear on a recording.

In "Why Mahler?" Lebrecht features an exchange between your Finnish countryman, Jean Sibelius, and Gustav Mahler. They apparently met one time in Finland. Sibelius, who had completed his own Third Symphony extolled the virtues of structural severity. Mahler countered Sibelius with his belief that the symphony must be like the whole world, insisting that a symphony must embrace everything.

And see what happened? Mahler died at age fifty-one and Sibelius (who stopped composing around the same age) lived into his nineties.

Mahler suffered from terrible hemorrhoids.

Mahler was a hemorrhoid. He treated his musicians horribly.

You most recently performed Mahler's Third Symphony, and without going overboard, I'd say your solos were divine. In this symphony, Mahler sought to explain the universe, to find a reason for suffering and misery in this world. Some believe the answer to solving the Mahler riddle might be revealed in Schopenhauer's "The World as Will and Representation," as Schopenhauer's philosophy captivated the composer. For Bernstein, the Third Symphony was not just a pastoral symphony—an answer to Beethoven, but an ecological prophecy. In 1967, Bernstein claimed that it is 'only after we have experienced the smoking ovens of Auschwitz, the frantically bombed jungles of Vietnam, through Hungary, Suez, the Bay of Pigs, the refueling of the Nazi machine, the murder in Dallas, the arrogance of South Africa, the Hiss-Chambers travesty, the Trotskyite purges, Black Power, Red Guards, the Arab encirclement of Israel, the plague of MacCarthyism, the Tweedledum armaments race—only after this can we finally listen to Mahler's music and understand that it foretold all'.

So tell me. What was your favorite moment in the performance of the Third Symphony?

When it was over.

Sunday, June 26, 2011

The Great Piano Heist

I ask my readers: do you remember where you were and what you were doing the day when the local press announced Music Director Gerard Schwarz's retirement from Seattle Symphony? Here's what I recall. I was bent over the kitchen sink peeling potatoes. The phone rang. A symphony violinist drew in a deep breath, paused, and calmly stated, "He's retiring."

I ask my readers: do you remember where you were and what you were doing the day when the local press announced Music Director Gerard Schwarz's retirement from Seattle Symphony? Here's what I recall. I was bent over the kitchen sink peeling potatoes. The phone rang. A symphony violinist drew in a deep breath, paused, and calmly stated, "He's retiring.""Who?" I asked innocently, but silently hopeful.

"Schwarz," she said. "June, 2011."

I can remember the wheels spinning in my head; 2011 would feel like an eternity, I thought to myself. It's probably not, dear reader, what you may expect. I waxed nostalgic for a few magic moments after the call, sentimentalist that I tend to be. I remembered some meaningful times from the past, mostly celebratory gatherings; baby showers and birthday parties; a Bat Mitzvah too. I was a mother with two young daughters, but also first chair and artistic director for the Northwest Chamber Orchestra, now defunct, as many other arts organizations will soon be. For example, Bellevue Philharmonic just folded after 43 years. I was also concertmaster of Pacific Northwest Ballet back in the glorious days of Artistic Directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell. My husband, Ilkka Talvi, served for twenty years as concertmaster for Seattle Symphony and Seattle Opera under Schwarz. Although my husband was an exemplary soldier, you won't hear much about his notable past from the departing one; the epaulets from his uniform were stripped by the commander for reasons that were never articulated, but can be deduced, judging from the outcome of his absence. But listen to the SSO recordings of Diamond and Creston on the Naxos label, with my husband as soloist, and you'll hear a fiddle player of top rank; one that inspired a warm, refined European sound from the strings.

The choice of Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony as a closing event might have proved symbolic. After all, in terms of morale, the Seattle Symphony—with many fine players—can now move forward to not only new leadership (the orchestra is simply not the same orchestra as it was when Schwarz first appeared on the podium back in the early 80s), but to a future of civility under the musical directorship of Ludovic Morlot, a 36 year old French violinist/conductor who has already directed the Chicago Symphony, Boston Symphony, and New York Philharmonic. Certainly, Maestro Morlot possesses a sensibility when it comes to strings, already eager to regroup first and second violins so that the two sections will blend and hear each other, rather than second guess from one end of the massive stage to the other.

Schwarz's tenure lasted exceedingly long (26 years) by industry standards; normal shelf life for a Music Director is about 7-10 years. The retaliation within the orchestra began to resemble a TV crime series, with alleged vandalisms, a dented French horn, and a razor blade found in a mailbox. But to the Seattle masses, Schwarz is an icon, and understandably so. A downtown street has been named after him. One that, I'm sure, many musicians will attempt to avoid, for the sign itself might just trigger a bout of post traumatic stress disorder. One retired musician will have a book completed by this summer's end as testimony to bullying in the orchestral workplace.

Life is never what it appears in the symphonic arena; you can be sure of that. Not a word of gratitude was exchanged after the final rehearsal between the departing one and his followers. Not a simple, "Have a great summer and future" or "Thank you, colleagues, for coping with my didactic approach, retaliatory measures of hiring and firing, not to mention the episode of withholding your bargaining contract from being ratified unless you agreed to my choice of principal horn." Oh yes, and not to forget the "declaration of loyalty to Gerard Schwarz" the principals were forced to sign back in 2002. (Without that declaration, the Schwarz era might have ended years ago, when his contract was up for renewal.)

With any cult of personality, audiences go wild. Think Adolf Hitler. I suppose the speeches at the final farewell were scintillating. I was told that the applause bordered on frenzy. Schwarz turned to the orchestra on stage—and publicly professed his love to each and every orchestra musician. I'm sure my colleagues felt the loving vibes, and reciprocated whole-heartedly.

Shall we take one final trip down memory lane?

So, what happened next after all the hoopla? Like any other employee, the departing one was required to clean out his office. Seems he went the extra mile with this, too, and performed an exemplary job. Nothing half-way. The Steinway grand piano, which Seattle Symphony claims belongs to the organization (uh-oh) and expects returned, was packed up along with everything else. If lightbulbs were pilfered along with rolls of toilet paper, you know tough times are ahead. Oh, and in case anyone's interested, there's a mansion for sale on Highland Avenue.

Reporting (still alive) from Seattle!

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

The Way of the Conductor

The faithful reader of my blog may wonder what activities I indulge in a few days after a stressful performance, as in down time or recalibration. It would be so easy to beat oneself up over a few silly mishaps during a live concert; thankfully I would never contemplate suicide like the accomplished Israeli violinist, Matan Givol. Matan's death saddens me greatly, though I never met or heard the young man play. I can't help but wonder if he struggled as many artists do—with depression and severe self-abasement. That's one of the reasons that artists must learn to lead a balanced existence with varied interests, and hopefully, find a meaningful personal life outside the professional. I hope, in some small way, that my blog is an encouragement to fellow artists.

I decided to pick myself up from the post-concert doldrums after the Beethoven Concerto episode and engage in one of my favorite past times: bargain hunting. If you happen to venture to our local Goodwill on a Saturday night, just before closing hour, you might find men dashing around in women's clothes and shoes. The atmosphere is fun and upbeat. Last Saturday I found a Mizrahi denim jacket for under five bucks! And the following day, I visited one of my beloved second hand book stores, "Twice Told Tales" in Fremont. There, while perusing the classical music books, I discovered a treasure: "The Way of the Conductor—His Origins, Purpose and Procedure" by Karl Krueger. I gazed at the title for a long while and thought to myself, I really didn't know that a conductor had a purpose or procedure...Although the book first made its appearance in 1958, you'd think it arrived fresh off the printing press with observations such as this one:

"There seems to exist today a far too general readiness on the part of the public—and among musicians, too—to accept the orchestra for what it was and too little awareness of its changing character in time and place---The few side lights on the orchestra's evolution which have been adduced make it clear that the orchestra either progresses or retrogresses, it cannot stand still."

There's a wonderfully thought-provoking section on the conductor's over-all influence on the orchestra.

"Assuming that an orchestra possesses mechanical mastery, its "sound" will be a projection of the conductor's musicality. And this "sound" is by no means a lasting phenomenon but, on the contrary, it is transitory and fugitive. It is indeed so fleeting that it is the first of the orchestra's characteristics to go when the conductor goes."

I wonder if this point might be somehow relevant for today's Philadelphia Orchestra. The Philadelphians, under the forty-four year tenure of Eugene Ormandy, and before that, Leopold Stokowski, at the height of its glory, was praised for its lush, opulent sound. I do not doubt that nowadays the ensemble resembles any other first rate orchestra; but I'm not sure it can compete with its own notable past. Which brings me to Stokowski's concept of sound and one of his trademarks: free bowing. You'll find in almost every orchestra (amateur ensembles, too) an almost anal fixation on string bowings (the back and forth motion of the bows—which go either down or up). Stokowski regarded this kind of exactitude as a mechanical effect, while his free bowing style resulted in an unbroken seamlessness and mellowness in the strings that attached itself to the Philadelphia Orchestra. In Stokowski's own words:

"Mechanism as one part of life is wonderful in an automobile or airplane, but not in art, which requires flexible pulsation. When string players are obliged to follow their section leaders and bow up and down bow in unison, they may attain the greatest precision but also the most rigidity and the least expressivity. There are occasions when this military type of uniformity produces just the right spirit, as in a Sousa March. The players of classical music are called upon to convey warmth and intensity and poetic passion which cannot be ideally realized when everybody bows together like robots."

But the tastiest meat of this book, "The Way of the Conductor" is dished up on the final page. I'll offer you a morsel before getting back to whatever-it-was-that-I was-doing to help recalibrate my life and boost mental stability. Young conductors, take note:

"The tyrant destroys, he stifles the invaluable aspiration of the individual player and tramples the unfoldment of his latent powers. And, by so doing, he robs a performance of undreamt-of values. No player can give his best when he is driven, it is when he is intelligently led that he finds himself."

I decided to pick myself up from the post-concert doldrums after the Beethoven Concerto episode and engage in one of my favorite past times: bargain hunting. If you happen to venture to our local Goodwill on a Saturday night, just before closing hour, you might find men dashing around in women's clothes and shoes. The atmosphere is fun and upbeat. Last Saturday I found a Mizrahi denim jacket for under five bucks! And the following day, I visited one of my beloved second hand book stores, "Twice Told Tales" in Fremont. There, while perusing the classical music books, I discovered a treasure: "The Way of the Conductor—His Origins, Purpose and Procedure" by Karl Krueger. I gazed at the title for a long while and thought to myself, I really didn't know that a conductor had a purpose or procedure...Although the book first made its appearance in 1958, you'd think it arrived fresh off the printing press with observations such as this one:

"There seems to exist today a far too general readiness on the part of the public—and among musicians, too—to accept the orchestra for what it was and too little awareness of its changing character in time and place---The few side lights on the orchestra's evolution which have been adduced make it clear that the orchestra either progresses or retrogresses, it cannot stand still."

There's a wonderfully thought-provoking section on the conductor's over-all influence on the orchestra.

"Assuming that an orchestra possesses mechanical mastery, its "sound" will be a projection of the conductor's musicality. And this "sound" is by no means a lasting phenomenon but, on the contrary, it is transitory and fugitive. It is indeed so fleeting that it is the first of the orchestra's characteristics to go when the conductor goes."

I wonder if this point might be somehow relevant for today's Philadelphia Orchestra. The Philadelphians, under the forty-four year tenure of Eugene Ormandy, and before that, Leopold Stokowski, at the height of its glory, was praised for its lush, opulent sound. I do not doubt that nowadays the ensemble resembles any other first rate orchestra; but I'm not sure it can compete with its own notable past. Which brings me to Stokowski's concept of sound and one of his trademarks: free bowing. You'll find in almost every orchestra (amateur ensembles, too) an almost anal fixation on string bowings (the back and forth motion of the bows—which go either down or up). Stokowski regarded this kind of exactitude as a mechanical effect, while his free bowing style resulted in an unbroken seamlessness and mellowness in the strings that attached itself to the Philadelphia Orchestra. In Stokowski's own words:

"Mechanism as one part of life is wonderful in an automobile or airplane, but not in art, which requires flexible pulsation. When string players are obliged to follow their section leaders and bow up and down bow in unison, they may attain the greatest precision but also the most rigidity and the least expressivity. There are occasions when this military type of uniformity produces just the right spirit, as in a Sousa March. The players of classical music are called upon to convey warmth and intensity and poetic passion which cannot be ideally realized when everybody bows together like robots."

But the tastiest meat of this book, "The Way of the Conductor" is dished up on the final page. I'll offer you a morsel before getting back to whatever-it-was-that-I was-doing to help recalibrate my life and boost mental stability. Young conductors, take note:

"The tyrant destroys, he stifles the invaluable aspiration of the individual player and tramples the unfoldment of his latent powers. And, by so doing, he robs a performance of undreamt-of values. No player can give his best when he is driven, it is when he is intelligently led that he finds himself."

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Questions and Answers for MKT

As I'll be making my long-awaited appearance this Friday evening as soloist for the Beethoven Violin Concerto with Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra, after an extended hiatus from concertizing, I decided to grant an exclusive interview. As this is the internet age, an artist no longer needs to wait for a reporter; this is the era of narcissistic self-promotion, remember? So I contacted the journalist myself, and as they say in the biz, made it happen.

Q: How does it feel to be returning to the concert stage? It's been what, 3 or 4 years?

A: Well, to tell the truth, it's a little scary...I mean, I've always had a tendency to freak out, as noted in my memoir, Frantic. And, like athletes, instrumentalists can atrophy. Also, we age.

Q: What are your fondest memories of performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto?

A: Well, I have two that leap to mind. The first, of course, was an appearance with Orchestra Seattle under the leadership of beloved George Shangrow at Meany Hall. I was amazed with George's musical intuition, for he was with me at every twist and turn. The other time—now this goes way back—was at Peter Britt Festival, where I served as concertmaster. I performed the Beethoven with James DePreist outdoors in 110 degree heat in Medford, Oregon. I glanced at my fingers which swelled to the size of sausages. Want to know a secret?

Q: I love secrets. Dish—

A: I was so intimidated by DePreist (but loved him and still do), that I begged: Don't you dare watch me during the cadenzas!

Q: Did DePreist oblige?

A: No. He peeked. Rascal.

Q: What is your regimen during the weeks prior to your performance?

A: I nibble on my nails, and read, read, read and listen, listen, listen and practice, practice and practice. Alternate between coffee and wine. Snack. In other words, I obsess furiously.

Q: I understand you're married to violinist, Ilkka Talvi, of Men and Music fame?

A: Yes!

Q: And? Does he offer suggestions? Musical expertise?

A: Oh indeed. He reminds me of the concert which he attended in Vienna of David Oistrakh performing the Beethoven Concerto. Ilkka counted no less than eight memory lapses at that performance. He reminds me of this repeatedly, to test my patience, because memory loss is one of my biggest fears. But Ilkka awakened me to the beauty of Fritz Kreisler's recording. And you know what? It has transformed my concept of the entire work. The transcendent humility, nobility, pacing, spirituality, and technical perfection. I'm profoundly indebted to Fritz Kreisler. I would drop everything to listen to that great violinist play. We're most fortunate to have those archival recordings available.

Q: What other performers have influenced your Beethoven concept, at least, recently?

A: Well, I went and played for my esteemed colleague, violinist Sharan Leventhal, while she visited the west coast. It's interesting. Sharan made a few comments that have really taken hold.

Q: Please. Continue.

A: The Beethoven Violin Concerto is a symphony, she said. Now I knew that, of course, but needed to be reminded—for strength and command. My playing was too submissive. Sharan dropped the magic word.

Q: Abracadabra?

A: No. Heroic. The concerto begins with a military drumbeat, which I liken to a heartbeat, because when I wake up in the middle of the night in terror, that's what I hear; my own rapid heartbeat. But you know, the mere concept of heroism turned my thinking around. I started digging through books on Beethoven. I'm reading Schiller's "Aesthetic Essays" as Beethoven himself did. I recognize now the triumphant spirit in the concerto. It's a testament for the human being who has struggled, suffered, and will emerge victorious in the end.

Q: You showed me the copy of your score. It's—well, quite messy.

A: Yes, I know. My mother was a collector of old sheet music, and I inherited this copy from her. You know, it's so old that the paper seems to dissolve in my fingertips. But, I love this edition. To me, it resembles a fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Beethoven brings me nearer to God. This is difficult to explain. Please excuse me for my rambling. That being said, my dear cellist friend, Daniel Morganstern, reminded me that the performance this Friday is not Judgment Day. And he told me to imagine that long entrance, the orchestra tutti, and practice the opening over and over again, to develop thought control.

Q: What is your opinion about the new group, Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra?

A: I feel very connected to this ensemble. The music director, Geoffrey Larson, is a major talent and a delight to work with. I might add that my former pupil, Andrew Sumitani, will be first chair for this concert. If I have a little trouble, maybe he'll just play my part?

Q: Really?

A: That was supposed to be a joke. In other words, I'm surrounded by good vibes.

Q: Any final thoughts?

A: Please join me Friday evening, May 20th at 7:30 with Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra at Seattle's Daniels Recital Hall for an evening of Haydn, Handel and Beethoven.

Q: How does it feel to be returning to the concert stage? It's been what, 3 or 4 years?

A: Well, to tell the truth, it's a little scary...I mean, I've always had a tendency to freak out, as noted in my memoir, Frantic. And, like athletes, instrumentalists can atrophy. Also, we age.

Q: What are your fondest memories of performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto?

A: Well, I have two that leap to mind. The first, of course, was an appearance with Orchestra Seattle under the leadership of beloved George Shangrow at Meany Hall. I was amazed with George's musical intuition, for he was with me at every twist and turn. The other time—now this goes way back—was at Peter Britt Festival, where I served as concertmaster. I performed the Beethoven with James DePreist outdoors in 110 degree heat in Medford, Oregon. I glanced at my fingers which swelled to the size of sausages. Want to know a secret?

Q: I love secrets. Dish—

A: I was so intimidated by DePreist (but loved him and still do), that I begged: Don't you dare watch me during the cadenzas!

Q: Did DePreist oblige?

A: No. He peeked. Rascal.

Q: What is your regimen during the weeks prior to your performance?

A: I nibble on my nails, and read, read, read and listen, listen, listen and practice, practice and practice. Alternate between coffee and wine. Snack. In other words, I obsess furiously.

Q: I understand you're married to violinist, Ilkka Talvi, of Men and Music fame?

A: Yes!

Q: And? Does he offer suggestions? Musical expertise?

A: Oh indeed. He reminds me of the concert which he attended in Vienna of David Oistrakh performing the Beethoven Concerto. Ilkka counted no less than eight memory lapses at that performance. He reminds me of this repeatedly, to test my patience, because memory loss is one of my biggest fears. But Ilkka awakened me to the beauty of Fritz Kreisler's recording. And you know what? It has transformed my concept of the entire work. The transcendent humility, nobility, pacing, spirituality, and technical perfection. I'm profoundly indebted to Fritz Kreisler. I would drop everything to listen to that great violinist play. We're most fortunate to have those archival recordings available.

Q: What other performers have influenced your Beethoven concept, at least, recently?

A: Well, I went and played for my esteemed colleague, violinist Sharan Leventhal, while she visited the west coast. It's interesting. Sharan made a few comments that have really taken hold.

Q: Please. Continue.

A: The Beethoven Violin Concerto is a symphony, she said. Now I knew that, of course, but needed to be reminded—for strength and command. My playing was too submissive. Sharan dropped the magic word.

Q: Abracadabra?

A: No. Heroic. The concerto begins with a military drumbeat, which I liken to a heartbeat, because when I wake up in the middle of the night in terror, that's what I hear; my own rapid heartbeat. But you know, the mere concept of heroism turned my thinking around. I started digging through books on Beethoven. I'm reading Schiller's "Aesthetic Essays" as Beethoven himself did. I recognize now the triumphant spirit in the concerto. It's a testament for the human being who has struggled, suffered, and will emerge victorious in the end.

Q: You showed me the copy of your score. It's—well, quite messy.

A: Yes, I know. My mother was a collector of old sheet music, and I inherited this copy from her. You know, it's so old that the paper seems to dissolve in my fingertips. But, I love this edition. To me, it resembles a fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Beethoven brings me nearer to God. This is difficult to explain. Please excuse me for my rambling. That being said, my dear cellist friend, Daniel Morganstern, reminded me that the performance this Friday is not Judgment Day. And he told me to imagine that long entrance, the orchestra tutti, and practice the opening over and over again, to develop thought control.

Q: What is your opinion about the new group, Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra?

A: I feel very connected to this ensemble. The music director, Geoffrey Larson, is a major talent and a delight to work with. I might add that my former pupil, Andrew Sumitani, will be first chair for this concert. If I have a little trouble, maybe he'll just play my part?

Q: Really?

A: That was supposed to be a joke. In other words, I'm surrounded by good vibes.

Q: Any final thoughts?

A: Please join me Friday evening, May 20th at 7:30 with Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra at Seattle's Daniels Recital Hall for an evening of Haydn, Handel and Beethoven.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Growing Pains