Perhaps the Young Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra from Seattle Conservatory of Music is on the right track. A self-governing group of highly skilled and motivated teen-aged musicians, they select their own programs, choose coaches, and host auditions. I happened to be present at one session and witnessed the process of voting in a new cellist. "Tell us about yourself," said one member of the committee. "How many years have you been studying cello and what school do you attend?" After a brief round of questions, the panel of young musicians voted, and chose to offer the cellist a position. What followed was a vigorous reading of Mendelssohn's Octet.

As I see it, this is the first step in broadening an awareness for future job skills and creating a new paradigm. While orchestras throughout the nation are undergoing a crisis of identity and dealing with economic uncertainty, conservatory students are encouraged to become entrepreneurs, and figure out ways to effectively manage arts organizations. How else to survive in the 21st century with the arts pushed to the periphery?

The Young Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra is learning about proprietorship along with the rudiments of ensemble playing. The musicians might take this valuable experience even farther by designing programs, creating discussion groups, and hosting post-concert forums. They might adventure into public speaking and creative writing as a means to connect with audiences. Economics, as in what makes an ensemble sustainable, should be integrated into the conservatory curriculum. The students might be asked to balance organizational costs with ticket revenue. Since the public sector can no longer be relied upon for regular hand-outs, and funding sources are strained, these youngsters might help to create an effective business model.

That being said, as I follow the news of Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and the impending strike or lock-out by the end of this week, I recognize the tell-tale symptoms of cultural-entitlement mentality. The veteran players are unwilling to accept work-rule changes, such as splintering into smaller groups and participation in community outreach for less compensation, even though their survival depends on it. At a time when the city is in desperate financial straits, supporting a symphony orchestra is obviously not top priority. Musicians who maintain they must be paid what they believe they deserve, regardless of what the rest of Detroit's society has endured by way of depressed economy, are deluding themselves. As the late Ernest Fleischmann, executive leader of the Los Angeles Philharmonic said in his 1987 commencement address to the Cleveland Institute of Music,"The orchestra is dead. Long live the community of musicians." DSO might replace the entitlement attitude with gratitude for having playing jobs. Besides, why would a cut in salary for a musician be any more devastating than for an auto worker?

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Sunday, September 19, 2010

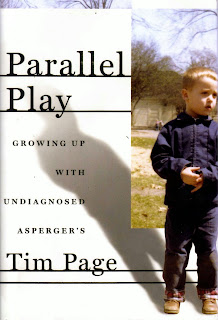

Parallel Play

I've always been attracted to intelligent people, or rather, geniuses. As far back as I can recall, I've been drawn to original thinkers, doers, and especially, the "quiet" type. But, I never thought to classify those rare individuals with any so-called disorder. Tim Page, who won a Pulitzer Prize as chief music critic for The Washington Post, was diagnosed at the age of forty-five with Asperger's Syndrome—an autistic disorder characterized by often superior intellectual abilities (such as all encompassing recall and computer-like retention) but also by obsessive behavior, ineffective communication, and social awkwardness. In his memoir, Parallel Play, Page reveals how the diagnosis helped him make sense of the loneliness and uncomfortable personality that marked him for life.

The chronicle of Tim Page's journey with Asperger's is fascinating, as it opens a window to a world that few understand. It is a condition which some consider a disability, but I would argue, a gift. It is speculated that Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton may have had Asperger's as both experienced intense intellectual interests in specific areas. Both scientists had trouble reacting properly in social situations and had difficulty communicating. The syndrome was identified in 1944, by Hans Asperger, a Viennese pediatrician who wrote, "For success in science or art, a dash of autism is essential."

In "Parallel Play," Page recounts his earliest memories as a child simultaneously young and old who sought refuge in music and books, a rebellious teen-ager easily prone to over-stimulation and morbid thoughts. The course of Tim Page's life shifted dramatically while attending a summer at Tanglewood. "Suddenly I had peers who (and sometimes shared) my obsessions, with whom I could discuss pieces I was learning on the piano, the compositions I was trying to write, obscure recordings, the proper way to dot a sixteenth note, and the dream of what Glenn Gould called the purpose of art—a gradual , lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity."

Tim Page concedes that many of the things he's accomplished were not despite his Asperger's syndrome but because of it. His book has provided me with greater insight and sensitivity for those isolated and afflicted by genius. And I take the opening quote of the book (attributed to Philo of Alexandria) to heart:

Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.

Words that a music critic should heed.

The chronicle of Tim Page's journey with Asperger's is fascinating, as it opens a window to a world that few understand. It is a condition which some consider a disability, but I would argue, a gift. It is speculated that Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton may have had Asperger's as both experienced intense intellectual interests in specific areas. Both scientists had trouble reacting properly in social situations and had difficulty communicating. The syndrome was identified in 1944, by Hans Asperger, a Viennese pediatrician who wrote, "For success in science or art, a dash of autism is essential."

In "Parallel Play," Page recounts his earliest memories as a child simultaneously young and old who sought refuge in music and books, a rebellious teen-ager easily prone to over-stimulation and morbid thoughts. The course of Tim Page's life shifted dramatically while attending a summer at Tanglewood. "Suddenly I had peers who (and sometimes shared) my obsessions, with whom I could discuss pieces I was learning on the piano, the compositions I was trying to write, obscure recordings, the proper way to dot a sixteenth note, and the dream of what Glenn Gould called the purpose of art—a gradual , lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity."

Tim Page concedes that many of the things he's accomplished were not despite his Asperger's syndrome but because of it. His book has provided me with greater insight and sensitivity for those isolated and afflicted by genius. And I take the opening quote of the book (attributed to Philo of Alexandria) to heart:

Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.

Words that a music critic should heed.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Sounds From Space

With arts organizations underway for the beginning of their seasons, and several in the midst of negotiations, not many economic sour notes have been reported in the press as of late. Fall is the season when organizations put on a happy face, and endeavor to bolster their subscriptions by portraying themselves as not just viable, but World Class, at least for as long as employees are paid in parity with others. What happens when salaries are lowered is anybody's guess. Wrong notes, missed entrances, intonation mishaps, less blend?

For those who have been following Detroit Symphony over recent months, the news is pretty grim. The two sides are locked in a bitter labor dispute with management proposing pay cuts of about 30%. Base salaries would shrink from $104,650 to $73,800. That's correct. You read those figures right. And even the mighty Philadelphia Orchestra is battling ways to avert bankruptcy after announcing an eight million dollar operating deficit: "In the coming months, a committee will fashion a new strategic plan for covering everything from what the ensemble plays, to where, for whom, and how often."

Which makes me wonder why everyone's spinning their wheels over a new business model when a solution could be gleaned from this morning's New York Times: Boeing Plans to Fly Tourists Beyond Earth. The flights, which could begin as early as 2015, would most likely launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida to the International Space Station. All it takes is just a bit of forward thinking to shuttle a symphony orchestra into orbit. I admit, with Boeing connections here in Seattle, and a local billionaire cosmonaut who donates millions of dollars to a falling meteorite, this community might have the upper hand. If an orchestra has a vision and a mission, why not ear-mark those campaign dollars for a concert series in space? Granted, it might need to be a chamber orchestra at first, or smaller crew to fit into the International Space Station. Naturally, the performances would need to be transmitted back to Earth in both audio and video.

Of course, nothing prevents überwealthy donors from constructing an orbiting concert hall. Launch those musicians, please, but warning: due to the necessary low air pressure, a conductor full of hot air might burst. What could be more ideal than performing "The Planets" on a space adventure? There's plenty of space music available already. How about commissioning a new work entitled "Symphony for the Planet of Apes?"

For those who have been following Detroit Symphony over recent months, the news is pretty grim. The two sides are locked in a bitter labor dispute with management proposing pay cuts of about 30%. Base salaries would shrink from $104,650 to $73,800. That's correct. You read those figures right. And even the mighty Philadelphia Orchestra is battling ways to avert bankruptcy after announcing an eight million dollar operating deficit: "In the coming months, a committee will fashion a new strategic plan for covering everything from what the ensemble plays, to where, for whom, and how often."

Which makes me wonder why everyone's spinning their wheels over a new business model when a solution could be gleaned from this morning's New York Times: Boeing Plans to Fly Tourists Beyond Earth. The flights, which could begin as early as 2015, would most likely launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida to the International Space Station. All it takes is just a bit of forward thinking to shuttle a symphony orchestra into orbit. I admit, with Boeing connections here in Seattle, and a local billionaire cosmonaut who donates millions of dollars to a falling meteorite, this community might have the upper hand. If an orchestra has a vision and a mission, why not ear-mark those campaign dollars for a concert series in space? Granted, it might need to be a chamber orchestra at first, or smaller crew to fit into the International Space Station. Naturally, the performances would need to be transmitted back to Earth in both audio and video.

Of course, nothing prevents überwealthy donors from constructing an orbiting concert hall. Launch those musicians, please, but warning: due to the necessary low air pressure, a conductor full of hot air might burst. What could be more ideal than performing "The Planets" on a space adventure? There's plenty of space music available already. How about commissioning a new work entitled "Symphony for the Planet of Apes?"

illustration from wired.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)